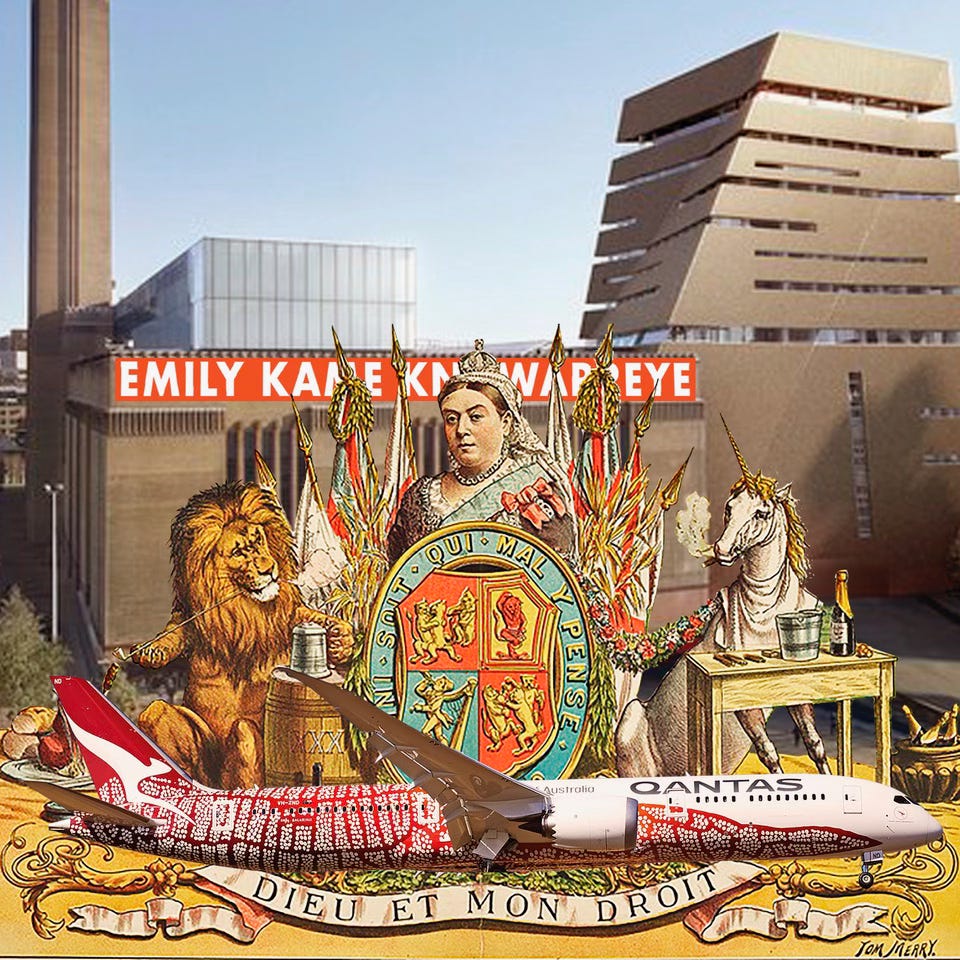

Australia has been free from Great Britain’s colonial yoke since 1901, but we still think like a colony. Having just returned from London where Tate Modern is hosting an important retrospective of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, it was only too obvious how much we value a little exposure in the Mother Country. The most basic reason may be that the Tate is a leading international showcase, whereas Australia – as people repeatedly tell me – is “so far away” from the rest of the world.

That may be true but there’s something a bit pathetic about the way we’ve responded to the Tate’s attention with a kind of slavish gratitude and a fatuous belief that Emily has “finally” made it onto the world stage.

Quite simply, Emily’s international breakthrough came in 2008, when Japanese curator, Akira Tatehata, moved heaven and earth to get her work shown in Osaka and Tokyo. It was the first (and last) time an Australian artist - let alone an Indigenous artist – has been the subject of a major retrospective at two top Japanese venues. The Tate show is undeniably important, but it’s remarkable how quickly the Japanese exhibitions have been forgotten.

Having seen the show in Osaka I can testify that it was bigger and better than the one held at the National Gallery of Australia in December 2023 and largely repeated at Tate Modern. It was also hung more imaginatively, with a sense of theatre that is missing from the London display.

The Australian curator responsible for the Japanese shows was Margo Neale, who also did the first big Emily retrospective in 1998, shown in Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra. I’ve written previously about the NGA’s inexcusable rudeness in not consulting with or even acknowledging Margo’s efforts or the crucial role that Tatehata played. The London show continues this exclusion, downplaying the Japanese shows and making it seem as if the Tate represents the first opportunity for the world to ‘discover’ this artist.

If the Tate show was an advance on the Japanese surveys there might be some slim justification for such professional discourtesy, but the current exhibition is inferior in almost every department. Unlike Margo Neale or Emily’s original dealer, Chris Hodges, the curators – Hetti Perkins and Kelli Cole – never knew the artist personally. They have sought advice from those with vested interests and ignored crucial people for reasons I can’t begin to fathom. I’d like to hear a convincing explanation from them as to why Emily’s largest painting, Earth’s Creation was excluded, along with the powerful last series of small paintings. Leave these works out and you are not showing the artist at her best.

These criticisms were raised in relation to the NGA show in December 2023, so there are no excuses for not addressing the problems. Absolutely nothing has been taken on board. Even the mistakes in the catalogue have not been corrected.

Just as disturbing is the Tate’s willingness to go along with everything the NGA has done. They didn’t bother to read the criticisms of the previous show, or if they did, simply chose to ignore them. They appear to have done no original research on the artist, merely accepting the NGA’s take on everything. They presumably felt confident the London reviewers would bill and coo about the show, no matter what it contained – or lacked. Given today’s oppressive identity politics who would be willing to criticise a show by an elderly Aboriginal lady? Besides, it’s almost certainly the only time they’ve seen Emily’s work on this scale.

The Tate took a complacent approach, believing that the NGA show was “good enough”, catering to their own convenience rather than the reputation of the artist. The NGA’s omissions were unforgivable, but the Tate’s bland acceptance of everything showed how little they really cared. They did, however, take the opportunity to congratulate themselves on being so committed to the First Nations artists of the world.

In this sense, Emily was a vital symbol of the Tate’s progressive ethos. In a seminar, curators, Gregor Muir and Kimberley Moulton portrayed the artist as a key figure in the museum’s opening up to the entire world, not just Europe and America.

Why then, didn’t they take the time to restore key works to the show? Why didn’t they insist that Emily’s relatives from Utopia should be present for the occasion? The lack of Aboriginal people at the opening was much commented upon, especially as it has become standard practice to make sure Indigenous people attend such significant overseas exhibitions. Didn’t the budget allow for such a trip, or was there nobody willing to look after the people from Utopia?

When I think of these events, I’m not sure whether the Tate’s casual self-regard is worse than the NGA’s curatorial insufficiency. Did the Tate have a duty to investigate and correct the problems of the original NGA show, or did the NGA have a responsibility to get things right in the first place? Either way, it’s an unsatisfactory result that does credit to neither museum. Most unsatisfactory of all is that they will probably get away with it, being happy to point to all those glowing reviews by London critics who don’t have much idea about what they’re looking at.

In other words, it will be a victory for appearances over reality. The institutions will take the credit but not recognise any of the issues. It underlines a growing problem: when nobody holds a contemporary museum accountable it will do whatever it likes, preferring spin over substance – relying on institutional status to win over an ignorant and incurious media.

It's a testament to the old colonial connection that the NGA is so much in awe of the Tate, and so ready to dismiss the value of those 2008 shows in Japan. For its part, the Tate has become accustomed to being shown due deference by the rest of the world. They control the much-desired showcase, and everybody else can only be grateful for whatever attention they choose to bestow upon them. I’m sure the Tate would dispute this description of their activities and motivations, but if the museum is without blame why did they simply accept the NGA’s version of reality without making the slightest attempt to assess Emily’s career?

In holding a major show of a leading Indigenous artist, today’s Tate would most probably see itself as helping to ‘decolonise’ the museum. As there is no precise agreement on what this term means, it may refer to hosting a particular exhibition; adding ‘First Nations’ names to wall labels; bringing in new protocols such acknowledging the elders or the Welcome to Country; or giving priority to Indigenous artists over those of European origins – as in the Australian government’s arts policy, which begins with the principle: First Nations first.

This may sound like an enlightened platform, full of good intentions, but I’m beginning to wonder if ‘decolonisation’ is nothing more than a form of re-colonisation.

Prior to the current obsession with identity issues and protocols there was a steady growth of sympathy for Aboriginal issues and an increasing recognition of the value of Aboriginal art. Today we’re faced with the spectacle of institutions falling over themselves to showcase Indigenous art at the expense of every other artform, often wallowing in guilt, shame and self-abasement in the process.

This approach is given official sanction in exhibitions such as Melbourne Uni’s 65,000 Years: A Brief History of Australian Art, which announces itself with the words: “This is an anti-colonial art exhibition”.

How far have we travelled from ‘colonialist’ thinking, when the spelling of an Aboriginal artist’s name can be changed on the authority of a white linguist in contradiction of that artist’s stated wishes? This is Primitivism revisited, or perhaps Primitivism lite. It suggests that Aboriginal people don’t have the same agency as their white counterparts. A linguist is empowered to take charge of the way a name is spelt, because she knows best. It’s a paternalistic gesture backed by academic authority.

How is it ‘decolonising’ not to have brought Aboriginal people from Emily’s community to the Tate opening? I’ve also been told that the documentary, Emily: I Am Kam, recently shown on SBS, filmed sites the local women expressly asked the filmmakers to avoid, causing much weeping when the film was shown.

All of these things attest to a ‘father/mother knows best’ mindset, not wildly different from colonial days, when the British or another European power took it upon themselves to grant the benefits of western civilisation to native peoples. They gave them different names, different religious beliefs and laws. They took their children away to give them ‘a better chance’ in life. Some of this was sheer brutality, much of it well-intended if misconceived, in accordance with the cultural norms of those times.

Our contemporary way of thinking pays exaggerated respect to First Nations peoples but somehow still seeks to arrange things for them, in line with our own ways of thinking. Authorities gush about Aboriginal people’s great spiritual knowledge but treat them like children.

Meanwhile, the old subservient relationship with Great Britain is perpetuated by the way we are thrilled by the Tate show but willing to forget about the equally important (and much better) shows held less than 20 years ago in Japan. Regardless of the way Australia’s foreign policies and immigration patterns have turned towards Asia in the wake of the Keating years, it’s the UK’s approval we still desire more than anything.

It's ironic that our benign but paternalistic attitude towards Aboriginal art, is echoed by Britain’s benign but paternalistic attitude towards Australian cultural institutions.

A reader recently sent me a link to a BBC radio “Essay”, A Museum in the Making, in which Gus Casely-Hayford, the director of the new V&A East, is in conversation with our own Lisa Havilah, the Great Helmsperson who has pushed through her personal priorities for the Powerhouse Museum ‘revitalisation’ in defiance of all expert and public feedback.

Gus is well-disposed towards Lisa and wants to believe they are both engaged in the visionary project of creating a new kind of museum for the 21st century. This suits Lisa’s way of thinking, but everything Gus describes about the V&A project simply highlights the huge incongruities with the Powerhouse.

For starters, the Victoria & Albert Museum is not demolishing its original, heritage-listed headquarters in Kensington, or turning it into a party venue under the guise of “revitalisation”. The project is a supplementary exercise which leaves the main venue intact.

The V&A was forced to seek new storage because its existing storage facility, at nearby Blythe House, is being reclaimed by the government. The PHM had an ideal, purpose-built storage facility in the Harwood Building, right alongside the museum in Ultimo, but the Havilah plan has seen that building emptied out and the collection carted off to Castle Hill in the far north-western suburbs. The Harwood has been handed over to a range of favoured ‘creative industry’ projects and is facing possible demolition. The V&A move was a necessity, the PHM’s, a choice.

The PHM’s Castle Hill building is similar to V&A East, or the Depot for the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, in that it is essentially a glorified storage facility. The innovative bit is that as well as making the collection more accessible to the public, this kind of building can also host projects, exhibitions and installations.

V&A East takes advantage of a “creative quarter” developed around the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Its neighbours include BBC Music, Sadler’s Wells, University College London, and the College of Fashion. The area is still well within London’s city limits, being less than 30 minutes by tube from Picadilly. To reach PHM Castle Hill from Martin Place by public transport will take more than an hour, with at least one change. Its only notable neighbour seems to be Western Sydney TAFE, or perhaps the Hillsong Church.

Despite Gus and Lisa’s willingness to make cheerful comparisons between the projects, the differences are more telling than the similarities. What’s most striking about this conversation is that Gus is speaking constructively about all the synergies and possibilities involved, while Lisa’s comments are often defensive and negative. She creates imaginary oppositions between generations, between the wealthy eastern suburbs and the neglected western suburbs, suggesting that until now, cultural infrastructure in Sydney ended at “the latte line”. When I looked up this “latte line”, it’s a socioeconomic construct that describes areas that have greater or lesser access to jobs, infrastructure and housing. Oddly enough, all three PHM venues are on the right side of the line, with places such as Fairfield and Penrith on the wrong side.

It's worth noting that this year Fairfield City Museum & gallery received a modest stipend of $150,000 in four-year recurrent funding from the NSW Ministry of Arts, while Penrith had its application knocked back. Three projects in Parramatta, by contrast, received a total of $1.23 million. As large parts of the grant announcements were kept secret, suspicion is rife that much of the money granted to individual projects will be funding the PHM by stealth, while established venues such as Penrith are now obliged to seek alternative sources of revenue.

Surely nothing could be more “latte” than Lisa’s policy of paying mates large salaries as PHM “associates”, or replacing curator-generated shows with celebrity choices, as we find with the current attraction at Castle Hill, where 28-year-old “actor and advocate”, Chloé Hayden, has been invited to choose a few of her favourite things to stick on a platform, on the scholarly basis of “I like it”.

According to Lisa Havilah, Chloé’s “unique perspective brings fresh insight to the rich stories embedded in textiles.” …As opposed to all those boring, stale perspectives brought to the subject by PHM curators who have been studying the collection for longer than insightful Chloé has been on the planet. Those dreary old curators – at least the ones who haven’t been killed off - have been relegated to the job of ‘fetch and carry’ in assisting the celebrity de jour.

Without going into further detail – partly because the BBC ‘Essay’ seems to have been taken down from its website – in the interaction between the two museum directors, Gus is ready to believe Lisa is achieving marvels because that’s what she has been telling him. In his enthusiasm to find international allies for his own way of thinking he has not looked into the background of the PHM ‘revitalisation’, not taken account of what has been lost or what the real outcomes might be, as opposed to abject fantasies such as the claims that PHM Parramatta will have 2 million visitors in its first year (not mentioned on the BBC Essay). I’m still not sure this isn’t a typo. They must have meant 200,000.

He's also willing to accept that Lisa got a million people through Carriageworks during her celebrated reign at that venue. But this figure could only have been achieved by counting everyone who turned up for Saturday markets, Fashion Week gatherings, Sydney Contemporary and Performance Space events. These fanciful numbers didn’t prevent her leaving Carriageworks on the brink of bankruptcy.

Even though his intentions may be positive, Gus is not doing Australians any favours with his uncritical acceptance of everything put in front of him in Sydney. I’m sure he’d be startled to hear it, but the ultimate nature of his response is patronising and disinterested. He is looking at the PHM through the lens of his own projects and ideas, not showing the slightest willingness to consider the monumental, ongoing criticisms of the PHM project.

Even though his own cultural roots lie in Ghana, Gus has unintentionally adopted the old colonial approach to Australian culture. He’s thrilled that a distant outpost of the former empire is doing such cool things and is quick to give his approval. So quick that it seems he hasn’t bothered to look into the pros and cons of the whole enterprise - just as the Tate couldn’t be bothered to look up the details of Emily’s career. He takes Lisa’s word for it, just as the Tate uncritically accepted the NGA’s version of Emily.

Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised at the relative indifference of UK museum professionals for what’s really happening in Australia. After all, we’re “a long way away”, and of marginal relevance to British culture. Where the former colonial power once guided and determined all our cultural choices, nowadays it is happy to take a quick look, give us a pat on the back, and tell us what a good job we’re doing. And we’re mighty chuffed to get such a nice report card! For the PHM and the NGA the approval of our UK superiors is incredibly useful in demonstrating to their state and federal political masters the quality of their work. “If the Tate and the V&A approve, we’re obviously on the right track.”

To believe this, and to hold up the UK as a model of international insight, is a sign that the colonial mentality is alive and well. From what I’ve seen first-hand, the UK institutions will say and do the positive thing but are not prepared to waste time looking into the substance of what’s going on in our museums. It might be argued that getting this right is the primary responsibility of local boards of trustees, relevant government departments – and most crucially, the press. In Australia today, none of these people are doing their jobs. We are wallowing in lies and secrecy, being made dizzy by spin, showing bland indifference about the bad decisions and dubious practices that are setting us up for a cultural and financial catastrophe.

The re-colonisation of Australian culture reveals the lack of intellectual and moral rigour shown by some of our institutions, who are happy to bend the knee to their British counterparts in order to get their unconditional approval. It’s pathetic that we are still craving acceptance in London while making a mess of things at home. When I asked a friend: “Why do you think these dumb, destructive things keep happening?” she said: “There’s an expectation of professionalism from the museums and galleries” – and that sounds about right. There is a general expectation that museums know what they’re doing and take a professional pride in the quality of their work. We’re willing to believe in this ideal of professionalism, even when the evidence is rapidly mounting that our institutions are acting in ways that represent anything but best practice. Today, more than ever, we need to hold fast to an ideal of professionalism and make sure it is actually being followed. The impetus won’t be coming from the heart of empire - we’ll need to find the will to do it for ourselves.

Coming back from my travels and fighting off the jet lag, I’ve posted two pieces this week: a column on Sydney artist, Eric Smith, whose work is being surveyed at the Macquarie University Art Gallery; and a film review of the Irish romance, Four Letters of Love. The Australian has also run my piece on the Emily show at the Tate, which I’ll post on this site next week. Although I’m constantly trying to stick to my own “expectation of professionalism”, travel tends to mess up the best-laid plans. Back in Terra Australis means getting back to the old routines.

Marvellous John.. thank you.