Last week we lost William Robinson, one of the giants of modern Australian art. There was a time I spoke with Bill regularly on the phone, but we’d lost touch in recent years. In person he grew even more elusive, as he became almost permanently cloistered in his house in Brisbane. When I once suggested that his works should be shown in China, he said, “Yes, but I won’t be going.”

Always of a cautious disposition, Bill hardly changed over the years. A tall, hulking figure, as bald as a bowling ball, he looked very much the same in his 80s as he had in his 50s. I always thought he was being too cautious about his health, but now that he has died, after a short illness, I’ll have to revise that opinion.

Bill gave the impression of being a man of few words, but he was formidably articulate when the occasion demanded. In 2005-06, when Ian Lloyd and I were putting together 61 artist interviews for the book, Studio: Australian Painters on the Nature of Creativity (2007), we had a standard 18 questions for everyone. Afterwards, I’d improvise, based on the artist’s responses. It soon emerged that the most successful artists were also the most clear-headed. Bill got through the questions faster than anyone else, giving a full set of precise answers in less than 30 minutes. He spoke as if he’d already prepared his replies in advance, although he had no inkling what we’d be asking.

It was a small glimpse of the painterly intelligence that informed all his work. He had thought long and hard about the artists he admired, from Chardin to Bonnard, taking what he needed from these influences. In the way figures seemed to float around his canvases, one saw a small trace of Ken Whisson, an artist of a completely different character.

It’s well known that Bill had to choose in his early years between being a painter or a concert pianist. As the story goes, he was so unsettled when the ABC concert orchestra took Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto at a different tempo to what he had expected, that he decided to become an artist. He would continue to play the piano every day, being a life-long acolyte of Bach and Schubert.

Bill was also a man of faith, although he never proselytised about his religious beliefs. Looking at his monumental Creation Landscapes, one can sense his immersion in the music of Bach, and his belief in a higher reality. God, nature and music were joined together in his painting in a way that no Australian artist has ever been able to match.

He was a slow starter, spending most of his life as an art teacher, only showing his work on rare occasions. When he had his first exhibition with Ray Hughes in Sydney in 1985, it was as if a fully formed Australian master had appeared in a puff of smoke. Nick Waterlow included him in the 1986 Sydney Biennale. Visiting American curator, Bill Lieberman, would purchase those works for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

If there was quiet profundity about Bill’s personality, another memorable aspect was a mischievous, self-deprecating sense of humour. This comes through most clearly in his riotous farmyard paintings, where he and his wife, Shirley, the cows, goats and chooks, are engaged in various forms of Breugelian mayhem. The portraits he submitted to the Archibald Prize were all gags at his own expense, as he didn’t feel comfortable painting other people. They were also filled with whimsical references to art history.

The Equestrian Self-portrait with which he won the Prize in 1987, was a parody of the trope of the Noble Rider, which has made its way down the ages. Rather than some classical or Napoleonic hero, this rider is portly and timid looking, without a set of reins to hold onto. It’s funny, but so beautifully painted it trounced everything else in that year’s competition. AGNSW director, Edmund Capon railed against the work, encouraging the media to portray Bill as a naïve painter – a Queensland goat farmer. Nothing could have been further from the truth, but it was a myth that would hang around for years. The artist himself seemed indifferent to these charges, perhaps feeling that it was just as good to be a farmer as a painter. The difference was one of degree: Bill was a very amateurish hobby farmer, but a dab hand with the brush. I suspect he rather enjoyed the disguise of “naivete”, which was more suited to his temperament than the pose of swaggering Bohemian genius affected by of some of his peers.

In his second Archibald Prize winner of 1995, Self-portrait with stunned mullet, Bill painted himself in wet weather gear, holding a fish. The telling detail was the little smile on his face, which had been borrowed from Hogarth’s The Shrimp Girl(1740-45). I can still laugh at the idea of Bill smiling into a mirror, striving to get this expression exactly right.

He was drawn into the limelight when his huge Creation Landscapes made their debut at the Ray Hughes Gallery in Sydney, in the mid-1990s. Nobody could ever view these pictures as the work of a naïve artist. They were like nothing ever seen in Australian art – a new way of depicting the rainforest as a window onto the cosmos. We had become accustomed to the idea of a typical Australian landscape being a bucolic scene with gum trees and billabong, or a harsh red desert. Bill had shown us an entirely new aspect of this country.

That series of huge canvases painted with small brushes, proved to be the peak of Bill’s career. He continued to paint landscapes, farmyard scenes, gardens and still lifes, but nothing would approach the Creation Landscapes for sheer scale and ambition.

I’m not much given to hyperbole, so when I say Bill Robinson was a great painter, I’m not merely writing in praise of a well-loved human being. He had that very rare ability to stop us in our tracks and compel us to look deeply into a canvas. He painted pictures that drew us into their depths and fired our imaginations. His place in Australian art history is carved in stone.

I feel saddened by his loss, but just as saddened by the woeful coverage his passing has received in the Australian media. Ten years ago, there would have been massive obituaries and full-page tributes. Today, as I scoured the Internet looking for articles, it was brought home to me the degree to which the mainstream media has almost given up on the visual arts and culture. Had Bill been a footy player or a cricketer, he would have received much more attention.

The Sydney Morning Herald ran an article in concert with the Age and the Brisbane Times, by Nick Dent, titled ‘Australia’s greatest artist’: William Robinson dies aged 89’. A pathetic little squib, cobbled together with a few dates and quotes, it was no more than the most perfunctory bit of journalism. It’s not the journo’s fault – it’s the slackness and indifference of the editors who have not been able to recognise Robinson as a figure of massive importance for Australian art. The ABC, The Guardian and The Australian were hardly more forthcoming. Bill’s death was treated as a small news item, not a major event that deserved detailed discussion and tributes.

I’ve never enjoyed writing obituaries, but I’ve produced a good many, largely through a sense of obligation to artists I knew and valued. During my last year at the SMH, I asked about doing pieces on Jan Senbergs, Anne Ferguson and Jutta Feddersen, all notable artists. None of those proposals was accepted. Since then, we’ve lost John Mawurndjul, Allan Mitelman and Kevin Connor, and as far as I can discover, none of them had the smallest notice in the SMH, or other mainstream outlets.

I can relate this to the neglect of The Diaries of Fred Williams 1963-1970, a long-awaited publishing event that didn’t receive a review in the mainstream press, let alone a feature story.

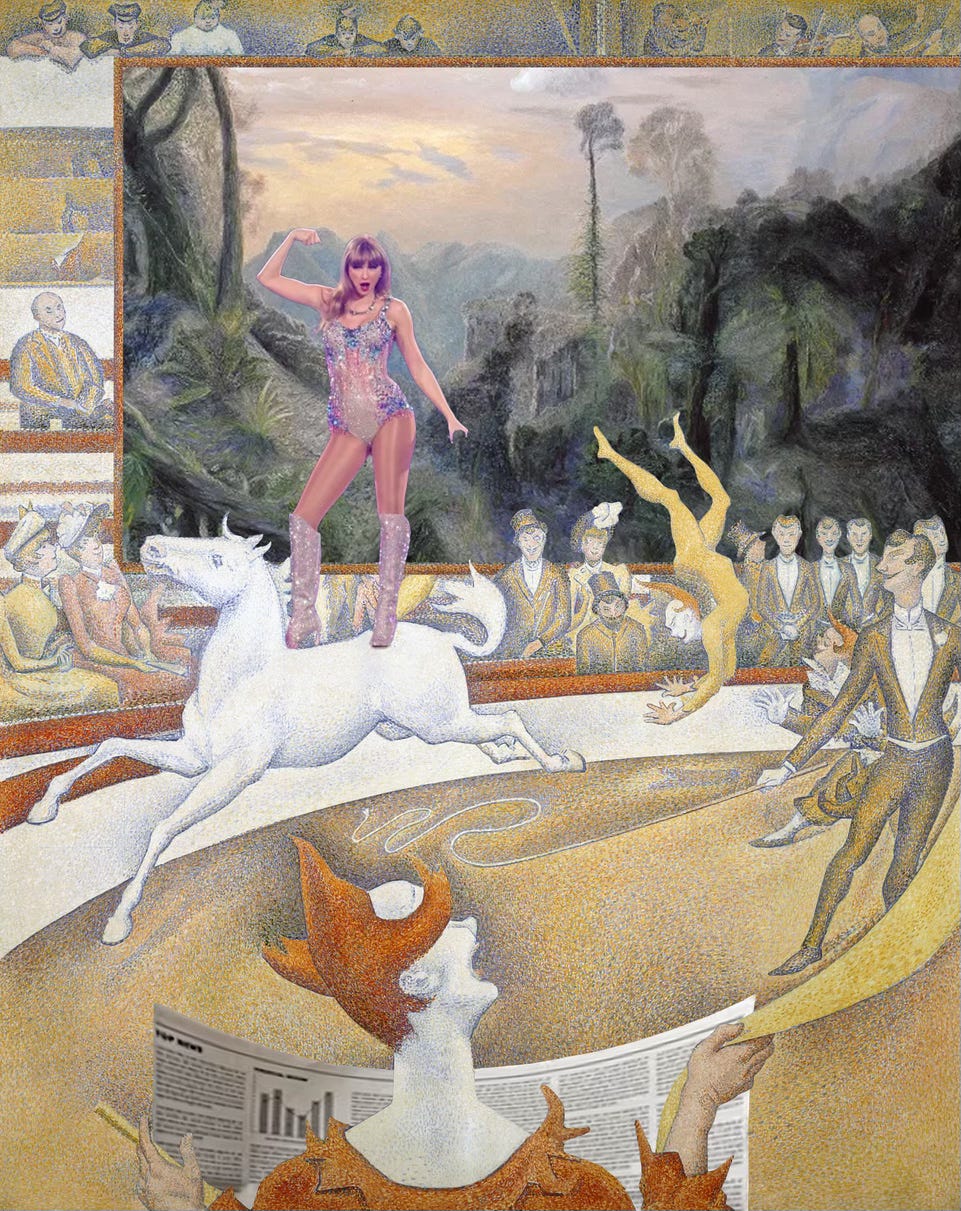

While the newspapers completely ignore the deaths of our most important artists, and the publication of major art books, they are stuffed full of idiotical articles on Taylor Swift or Sabrina Carpenter or some other pop star or rising actor. What is going on?? Even if the papers have largely divested themselves of writers who knew these artists and could speak about them with some authority, that’s no excuse for not reaching out to someone to put together a proper tribute, feature or obituary.

These are not simply dark times for culture and for quality journalism, they are disastrous times: a triumph of trash, a festival of ignorance, a celebration of superficiality. The work of an artist’s entire life is not judged worthy of displacing one of the multiple articles about Taylor Swift’s new album, or her engagement. But why talk about displacing anything? There’s ample room online to run the pop culture junk along with articles that anyone with a genuine interest in the visual arts might want to read. The problem is that no-one in the editorial ranks is interested or knowledgeable enough to recognise what needs to be done. Who do they think their audience is? Teenagers? The young-at-heart? The incorrigibly shallow? This must be the reason why they run so many stories telling us what to read, what to see, where to dine, etc. usually in the form of shopping lists. No wonder people are still telling me they are cancelling subscriptions to the NINE newspapers out of sheer frustration.

Bill Robinson’s passing has received more attention than the deaths of most of his peers, but more than nothing is no great landmark. This country has fallen into a sick decline when it comes to cultural matters, and it’s starting to have a big impact in terms of funding, as governments feel no necessity to put money towards museums and galleries, and private sponsors look for more productive ways to spend their surplus wealth. We need to take stock of this ongoing train wreck before the damage is beyond repair. I don’t hold out any hope for NINE media, with the honourable exception of the Australian Financial Review. While The Australian has some great moments, any story it runs is automatically shunned by its competitors, who don’t seem to be able to separate the facts of a case from their animosity for Rupert Murdoch. Instead, they are stubbornly pleased to grab the wrong end of every stick.

If anyone should take the lead it’s the ABC, which has the scope and resources – let alone an obligation under its charter! – to provide more in-depth coverage of the arts. At present it is doing a miserable job, ignoring important matters, churning out puff pieces on pop culture topics, avoiding critical engagement as if it were radioactive. As Chairman, Kim Williams, has been outspoken in his defence of criticism and the arts, isn’t it about time we saw some action? No-one can hope for much from the debased commercial mainstream, but the ABC is a different matter. The mission for the ABC is simple: Show leadership and regain much-needed credibility. Compete with the commercial product and it’s a race to the bottom that can only be lost.

Speaking of criticism, this week’s art column returns to the Emily Kame Kngwarreye saga, in the firm of a review of Classics from the Golden Age of Utopia at the S.H.Ervin Gallery. The show brings together a range of high quality works by Emily and other leading Utopia artists, and asks why these pictures weren’t included in the current show at Tate Modern in London. It’s only one of the questions the media should be asking if it had the slightest interest in the well-being of the arts.

This week’s movie is Honey Don’t!, the second in a trilogy of “lesbian noir comedies” by Ethan Coen, in collaboration with his missus, Tricia Cooke. It’s entertaining but scrappy, making us long for the day when Ethan and his brother Joel get back together. Don’t be surprised if this deliberate B movie gets more column inches than the entire roll call of Australian artists we have lost this year.

Vale, William Robinson, 16 April 1936 – 26 August 2025

Thank you for this article highlighting the cultural desert we find ourselves in when such agreat artists passes without the public recognition being given to their contribution to the arts. I have always been in awe of Robinson's work since a friend and I saw his energetic, playful intimate farm yard pictures in Ray Hugh's gallery. Many years later I was blown away by those large kaleidoscopic mountain landscapes that seemed to take one on a round trio down into them. May he rest in peace.

Thank you John, I share your views about Bill Robinson and I too was staggered at the lack of response to this great loss to Australian art.