During the pandemic of 2021 an exceptional group of French Impressionists travelled to Australia but barely got out of their crates. Nowhere in the world have artists such as Monet, Renoir, Degas and Cezanne had such a dismal reception, although the National Gallery of Victoria was more than willing to roll out the red carpet.

In June, in what must be a first for local museums, the NGV will restage the show that misfired four years ago. The Impressionists are once again leaving their home in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), and taking the voyage to Melbourne, for this year’s Winter Masterpieces exhibition. The return season is an extraordinary act of good will on behalf of the MFA, where many of these works are normally on permanent display. It’s a testament to the depth of Boston’s holdings that they can fill the gaps with similar pieces.

I travelled to Boston earlier this year, where I spoke with curators at the MFA, and had the privilege of visiting the conservation lab to see paintings by Degas and Monet out of their frames. It was a memorable experience to view Degas’s father listening to Lorenzo Pagans playing the guitar (c.1869–72) and Monet’s Boulevard Saint-Denis, Argenteuil, in winter (1875) in this way, as they seemed more self-consciously modern.

This was because we are accustomed to always seeing Impressionist paintings in hand-carved 18th century frames that have become permanently associated with the movement. It was the frames that allowed legendary art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, to sell these pictures to wealthy but hesitant clients. By virtue of imaginative repackaging, radical, ‘half-finished’ daubs were magically transformed into important works of art. The most eager buyers were wealthy American collectors who would eventually donate their paintings to institutions such as the MFA.

One of the oldest and largest museums in America, the MFA was founded in 1870, nine years after the National Gallery of Victoria. Despite the head start, Melbourne has never been able to compete with Boston in terms of private support. Maureen Melton, who holds the unique position of museum historian and archivist, tells me: “We have half a million works in our collection, and every one of them either came to us directly from the collector who owned it, or was purchased with funds from a donor. We get zero public money for acquisitions and never have had public money.”

There could be no more dramatic illustration of the contrasting public cultures of Australia and the United States. The NGV, which boasts the biggest and best art collection of any Australian museum, has 76,000 works in the collection, and has always been vitally dependent on government funds.

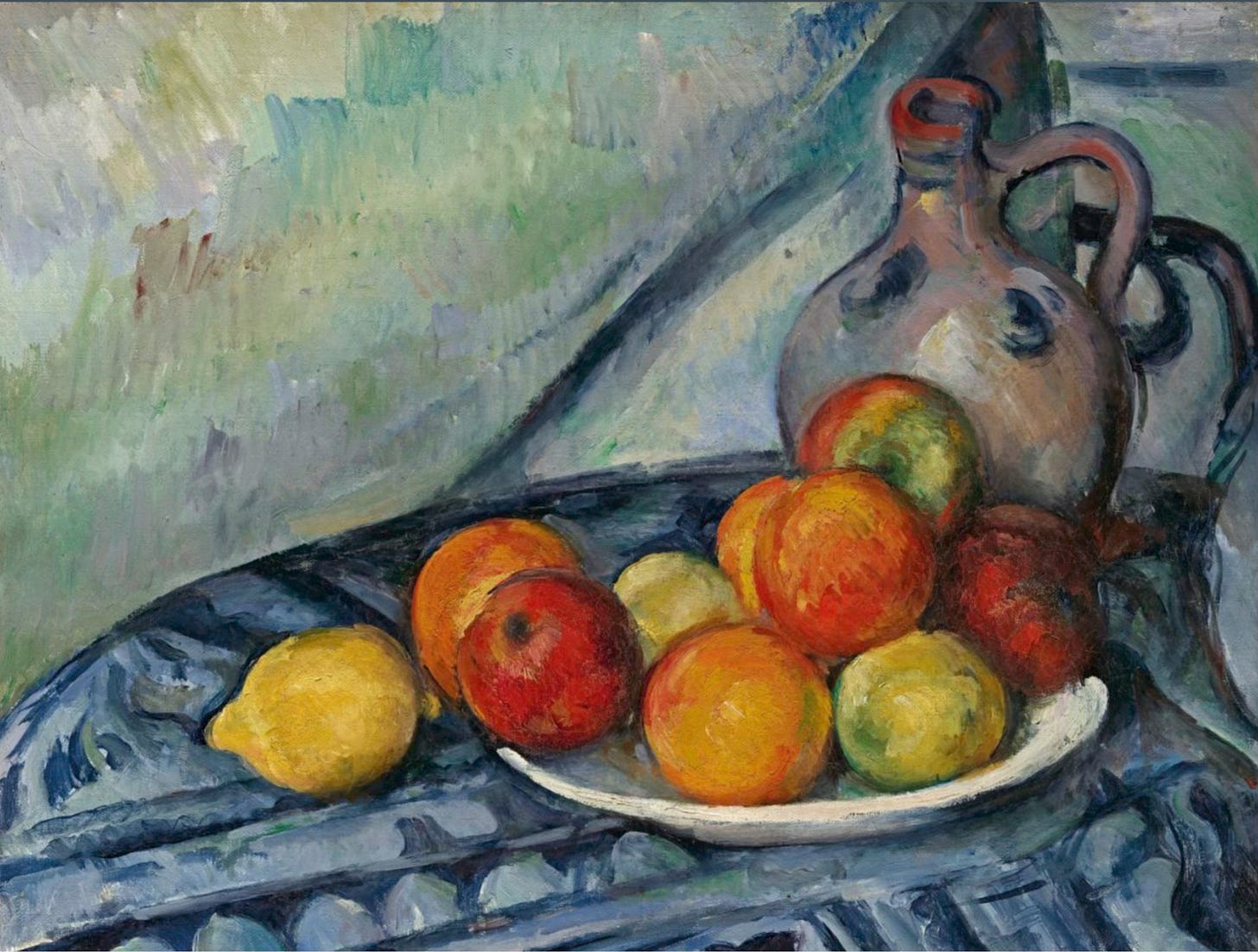

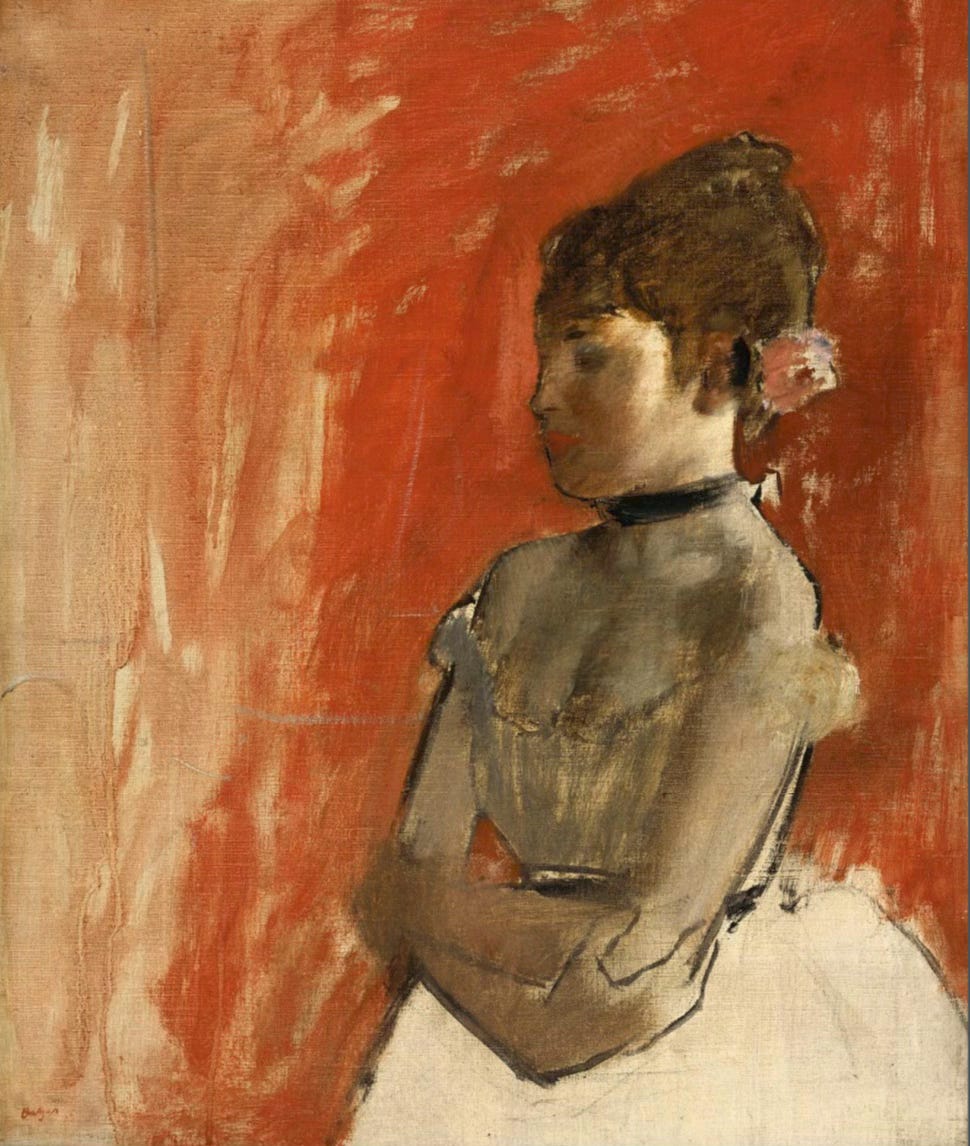

Melton has spent years researching not just the works in the collection, but the donors. She tells me about John Taylor Spaulding, heir to a sugar refinery, who became an obsessive collector of Japanese prints. By 1920 this had led Spaulding to the Impressionists, his first purchase being Degas’s Ballet dancer with arms crossed (c.1872). This work is coming to Melbourne, along with another 19 pictures from the Spaulding bequest, including one of the show’s indisputable masterpieces, Cezanne’s Fruit and a jug on a table (c. 1900-04).

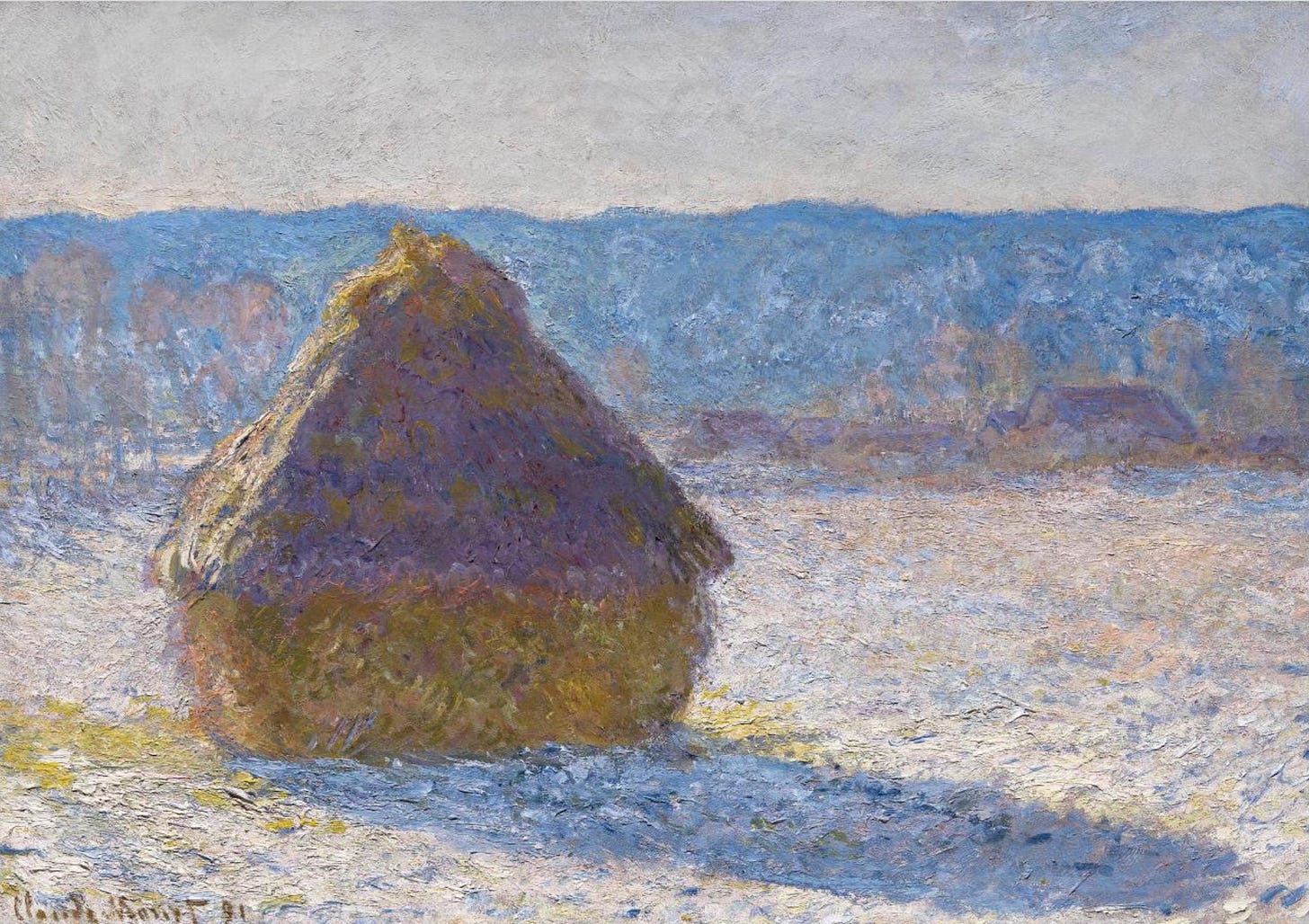

Another work Melton points out is the so-called “Honeymoon Monet”. The painting, Grainstack (snow effect) (1891), was purchased by Horatio Appleton Lamb, and his new wife, Annie (née Lawrence Rotch), on their honeymoon. “Lamb’s sister was an artist studying in Paris,” says Melton, “and she said to her brother: ‘You have to see the Grainstacks show!’” The couple were so impressed they spent all their wedding money acquiring the picture. In 1970, the Lamb family would gift the work to the MFA in memory of Horatio and Annie.

NGV curator, Miranda Wallace, says the Grainstack is the only painting the Melburnians specifically requested, as they wanted a “snow” picture for their Winter exhibition. The rest of an “exceptionally generous” selection of more than 100 works, was proposed by the MFA. No fewer than 19 of the museum’s 35 Monets will be travelling to Melbourne.

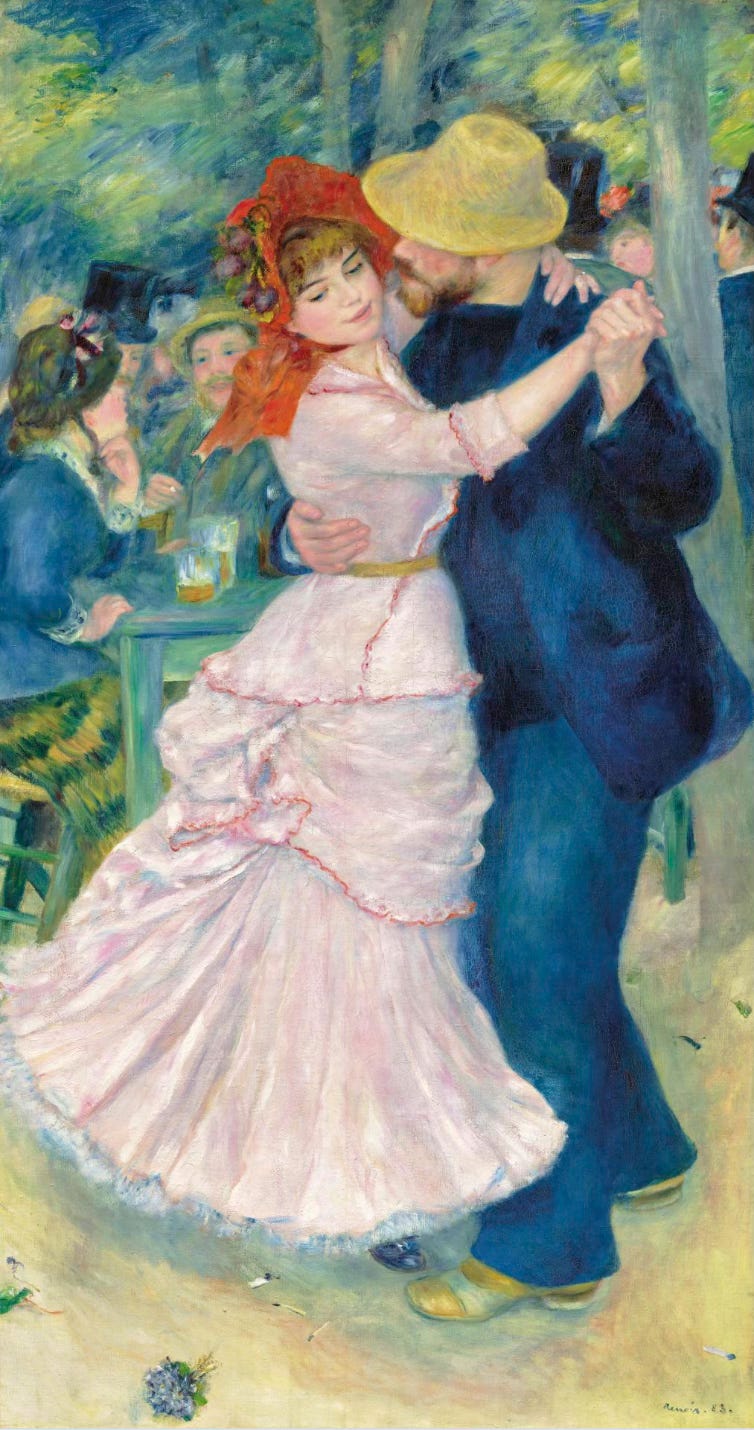

Renoir’s Dance at Bougival (1883), is expected to be the most popular work on display. It’s a depiction of simple pleasures, showing a worker in a cheap blue suit dancing with his sweetheart under the trees in a tavern courtyard. There’s beer on the table, cigarette butts and a lost corsage on the ground. One can almost hear the raucous music and the buzz of conversation. Take a sniff, and you can smell the stale booze, fags and sweat. The Dance is smaller than Renoir’s other tavern scenes, but one of his best-loved paintings.

For Katie Hanson, curator of European Paintings at the MFA, the biggest problem for organisers was the sheer popularity of the Impressonists. “When artworks are on T-shirts and posters and coffee mugs,” she says, “they become so familiar we almost stop seeing them. We were looking for a way to humanise the art by bringing back the voices of the artists, not taking for granted those things that are so familiar.”

Wallace says the emphasis on the artists’ voices is at once valuable and hard to achieve in an exhibition context. “We didn’t want to have endless quotes on the walls or the labels, but we’ve done as much as we can to let viewers know who these artists were, and how they thought.”

It might, in Hanson’s words, come down to a few simple ideas. “If Renoir gave the same life to the figure that Monet gave to the landcape, that had something to do with who they were as human beings. Where Monet craved solitude, Renoir preferred sociability.”

There’s also the realisation, explored in a diverse group of paintings, that Renoir, despite his insistent joie-de-vivre, his colourful palette and energetic brushstrokes, was tortured by insecurities.

“He worried about his own abilities and what steps to take next,” says Hanson. “Such worries are really relatable. It’s important we can share that aspect of these great artists and realise it wasn’t easy.”

The show also sheds light not just on the star artists but on a leading member of the supporting cast - the model, Victorine Meurent, who features in Manet’s two most famous works, Olympia (1863) and Luncheon on the grass (both 1863). Not only does the exhibition feature two of Manet’s portraits of Meurent, it includes the model’s Self-portrait of 1876.

Meurent (1844-1927) was not only a model, but an artist, an actor, a musician and a can-can dancer. The self-portrait was found by an art dealer at the Parisian flea market, Porte de Vanves, in 2010, and sold to the MFA in 2021, too late to be included in the first version of the NGV exhibition. For Wallace, this modest, previously unknown picture, is “one of the most exciting things in the show.”

Among so many works by famous painters, the Meurent self-portrait helps bring out what Hanson calls “the human dimension - the men and women behind the works of art – their moments of triumph, their moments of anxiety, their friendships, their squabbles.”

Young and old, rich and poor, working class and bourgeois, there was nothing homogeneous about this group of artistic rebels, aside from a shared desire to abandon mythology, literature, and idealised landscapes, and paint the world around them. Their embrace of modernity which seemed so radical in the 1870s, is now a source of pure joy to millions.

French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

National Gallery of Victoria

6 June – 5 October 2025

Published in the Australian Financial Review, 29 May 2025